Variety is the spice of life

Varied Practice in Music

In 1978, there was an interesting experiment conducted to investigate the impact of various types of practice on skill development in children (Kerr & Booth, 1978). This particular experiment (often called “The Beanbag Experiment”) involved a group of children who threw beanbags into buckets from a set distance.

First, the children were divided into two groups. One group practised throwing their beanbags from a distance of 3 feet from the target. This group was labelled the “specific” or “blocked” practice group.

The other half of the kids mixed up their practice and threw from two different distances, from 2 and 4 feet away from the target. This was the “varied” practice group.

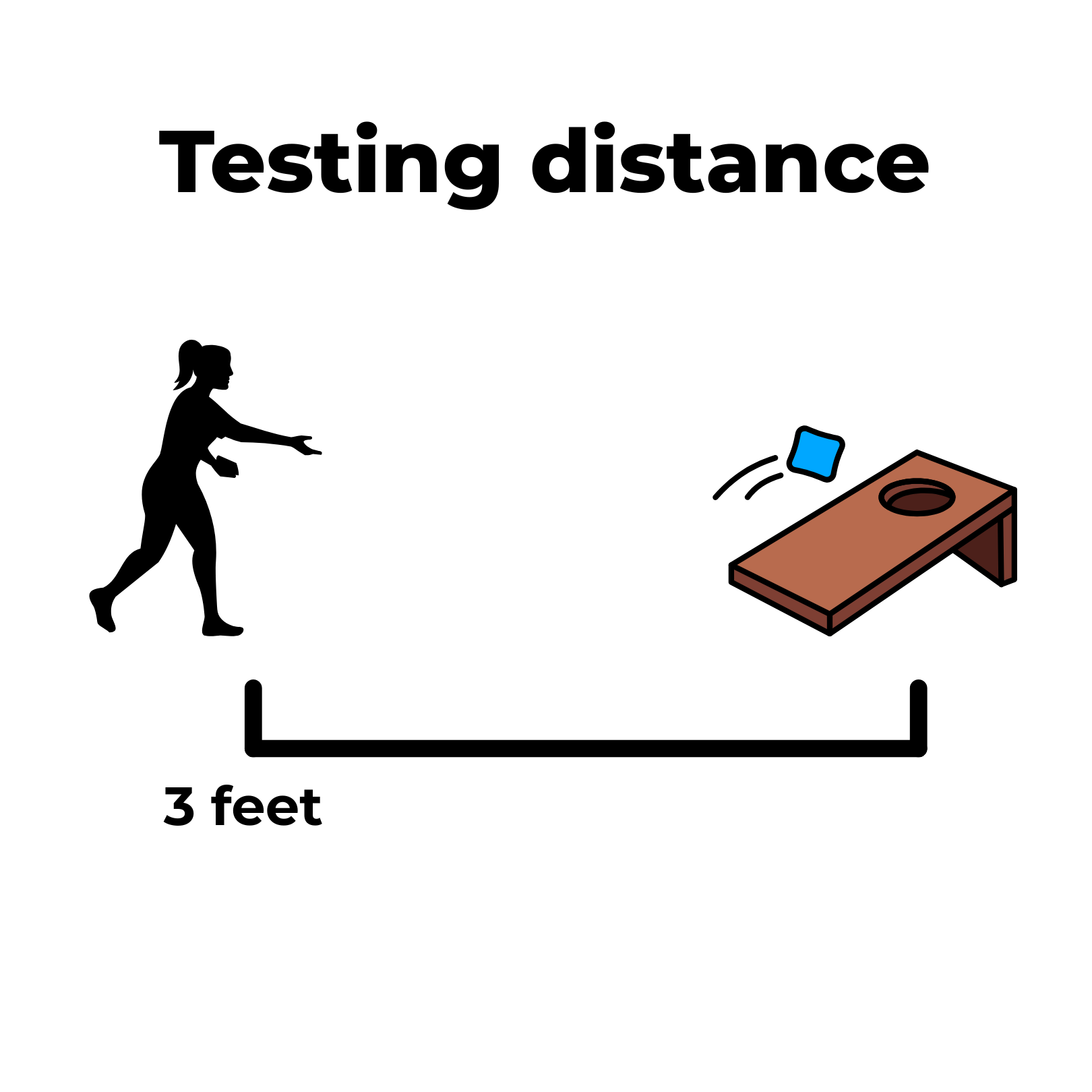

After 12 weeks of practice, both groups were then tested at a distance of 3 feet from the target. The blocked practice group had only practised from this distance, whereas the varied practice group had never practised from this distance.

So, which group do you think achieved the best results in the final test?

The results might surprise you, but the varied practice group performed MUCH better, even though they had never practised from the testing distance! 😲

Why did this happen? 🤔

Our brain absorbs more information and strengthens memory better when change and variability are incorporated into skill development.

While it might seem counterintuitive that the varied group performed better, this experiment teaches us a lot about how we learn and develop skills. This particular experiment examined motor skill development, but further research has shown the same results apply to cognitive learning as well (Shea & Morgan, 1979; Schmidt & Bjork, 1992).

👉 Watch the beanbag experiment explained here:

Why Variety Fuels Learning

One way of understanding why learning happens this way is to view it from a human evolutionary perspective. Humans have survived for hundreds of thousands of years because our brains have adapted to be alert to threats or changes in the environment around us.

As soon as our environment remains the same, your brain recognises that you're safe and there's nothing to worry about. When that happens, you relax into your comfort zone, and the parts of your brain responsible for learning begin to switch off.

In the practice room, the same thing happens when you repeat the same exercise in the same way each time. With constant repetition, your brain quickly loses interest and begins to disengage. This is where the term “mindless repetition” comes from.

Instead, by adding variability, you create the kind of conditions that keep your brain switched on and ready to learn.

Contextual Interference

Researchers Shea and Morgan (1979) found that practising in a random or mixed order (high contextual interference) often feels harder in the short term but leads to better long-term retention compared to practising in a fixed order (low contextual interference).

For musicians, this might mean mixing up scales, pieces, or bowing patterns rather than working through one thing repeatedly. While it feels less smooth and polished during practice, you are actually laying the groundwork for stronger, more flexible skills.

For more information about mixing up your repetitions, download a copy of my booklet on Interleaving 👆

Learning vs Performance

One of the biggest traps musicians fall into is confusing performance in the practice room with actual learning.

Blocked repetition often gives the illusion of progress because you sound smoother in the moment. Researchers refer to this as the “performance effect” – it appears as though you’re improving, but the learning is shallow (Soderstrom & Bjork, 2015).

Varied and unpredictable practice, on the other hand, might feel clumsy, but it builds deeper memory and adaptability that transfers to real performance.

Desirable Difficulty

In 1994, researcher and professor Dr Robert Bjork introduced the concept of “desirable difficulties” as a method to enhance learning outcomes. These are challenges during practice sessions that may slow the perceived rate of learning (because they make the learning conditions more difficult), but they lead to stronger retention of information and improved performance later on (which makes these learning conditions more desirable, hence the term “desirable difficulties”).

Varied practice is a perfect example of this. By mixing things up and adding variations to your repetitions, you force your brain to work harder in the short term, while building more robust and flexible skills for the future (Bjork & Bjork, 2011).

👉 Watch Dr Robert Bjork explain desirable difficulties

Don Bradman – A Master of Varied Repetition

One of the greatest examples of varied practice comes from outside of music: Sir Donald Bradman, widely considered the greatest cricket batsman of all time.

Growing up in rural New South Wales, Bradman famously practised by hitting a golf ball with a cricket stump against a curved water tank. The ball would rebound at different and unpredictable angles, forcing him to react instantly. By using a cricket stump (which is much thinner than a cricket bat), and golf ball (which is much smaller than a cricket ball), this made the the level of difficulty in his practice much greater, which honed his skills and precision better than if he simply used an ordinary cricket bat and ball.

Bradman also commented that the variability and unpredictability kept his training engaging and game-like, while sharpening his adaptability and accuracy. His genius and unbelievable skills weren’t just in his natural abilities – it was in how he practised by using varied repetition that made him the greatest batsman of all time.

👉 Watch Bradman’s training in action

Mimi Zweig – Practising in Rhythms

In music, world-renowned violin Professor Mimi Zweig (Indiana University) demonstrates the power of varying rhythms in practice in the video below. By changing rhythmic groupings, students stay mentally engaged and avoid mindless, autopilot repetitions.

This method improves flexibility, accuracy, and confidence – exactly what is needed for the unpredictability of performance.

👈 Watch Mimi Zweig’s rhythm practice demonstration

Benefits of Varied Practice

Implementing effective strategies can significantly enhance musical learning and performance. Varied practice is so useful in the practice room because it:

Strengthens neural connections and improves long-term retention (Schmidt & Bjork, 1992)

Encourages adaptability for unpredictable performance situations (Bjork & Bjork, 2011)

Improves awareness of musical similarities and differences, building interpretation and creativity

Increases engagement and reduces boredom by creating novelty in practice

Creates the right conditions for “desirable difficulties” that deepen learning (Bjork, 1994)

How to Apply Varied Practice

Here’s a practical way to make varied practice part of your routine:

1. Write down some individual variations of the core elements of music on small pieces of paper. Some variations you could write down might be:

Dynamics (pp, p, mp, mf, f, ff, < or >)

Articulations (staccato, tenuto, legato, accented, etc.)

Tempos (Adagio, Andante, Allegretto, Allegro, Presto)

Patterns (3rds, 4ths, 5ths, 6ths, 7ths, octaves)

2. Place each category of variations into separate containers, ie. Dynamics in container 1, Rhythms in container 2, etc.

3. During practice, pick one piece of paper from a container at random.

4. Apply the chosen variation to a scale, passage, or excerpt.

5. To increase the challenge, combine two or more variations at once.

This simple system turns practice into a game-like experience while keeping your brain alert. What might start as a basic C major scale suddenly becomes an unpredictable challenge that develops adaptability and performance readiness.

Key Takeaways

Repetition alone doesn’t guarantee learning – variability does.

Struggle in practice often means stronger retention later.

Randomness keeps your brain alert and ready to adapt.

Turning practice into a game makes it more fun and more effective.

Have fun experimenting with this approach – and let me know how it changes your practice!

References

· Bjork, R. A. (1994). Memory and metamemory considerations in the training of human beings. In J. Metcalfe & A. Shimamura (Eds.), Metacognition: Knowing about knowing (pp. 185–205). MIT Press.

· Bjork, E. L., & Bjork, R. A. (2011). Making things hard on yourself, but in a good way: Creating desirable difficulties to enhance learning. Psychology and the Real World, 2, 56–64.

· Kerr, R., & Booth, B. (1978). Specific and varied practice of motor skill. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 46(2), 395–401.

· Schmidt, R. A., & Bjork, R. A. (1992). New conceptualizations of practice: Common principles in three paradigms suggest new concepts for training. Psychological Science, 3(4), 207–217.

· Shea, J. B., & Morgan, R. L. (1979). Contextual interference effects on the acquisition, retention, and transfer of a motor skill. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Memory, 5(2), 179–187.

· Soderstrom, N. C., & Bjork, R. A. (2015). Learning versus performance: An integrative review. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 176–199.